4 Unexpected Things I've Learned from Starting a Nonprofit

Today I'm delving into the tried and true list format. Let's see how it goes!

1. A Fancy Degree Will Only Get You so far in the Marketplace of Ideas.

Over the course of the last several months, I've had the experience of working with some extremely bright people. Many of these people have multiple letters after their names, such as "Ph.D," "M.S.," "M.B.A.," "P.G.," and "P.E.," to name a few. Without a doubt, their qualifications are great, and their experience is often first-rate. However, when I was pitching the concept of Blueprint Earth to many of these fine folks, without fail I would stumble into their individual fear zones. A geologist, for example, would say something to the effect of, "Well, the geology side of things will be straightforward, but how on earth will you organize your data? That's impossible!" A data specialist might say, "The data will be simple. There's no way you'll be able to get a true representation of the animals in your area, though!"

I find that this type of reaction can be boiled down to one simple principle: fear of the unknown. It's natural, and it's rational for us as humans. What it does, unfortunately, is constrict the exploration of ideas outside of one's comfort zone. At Blueprint Earth, we've made a huge effort to stress that our mission is much, much larger than any one person. When I remind my beleaguered geologist or my skeptical data expert that we have a veritable small army of talented, resourceful experts in the very areas they're worried about, the fear passes. Remember, a degree means someone is extremely knowledgeable about one particular area. Asking for help when something is outside of that knowledge base is essential. That's a nice segue into my next observation.

2. Asking for Help Becomes a Way of Life.

I've been many things over the years in addition to my work as a geologist. I've also been a photographer, archivist, veterinary technician, sales exec, newspaper advertiser, horse riding instructor, and more. While that may seem like a good breadth of professions, it really doesn't even scratch the surface of all of the different types of expertise I needed when I started Blueprint Earth. I was fortunate enough to have my husband Carlos as my co-founder, and he has a very strong background in finance and business, and is a veteran of starting a few companies of his own. The nonprofit world shares many similarities with for-profit ventures, but there are many, many distinctions. We knew right away we'd need help. Fortunately for us, we both have healthy professional and personal networks, and we drew heavily on both of those groups to form our Board of Directors. Included in my personal network was Michelle Chaplin, who is a nonprofit professional. Michelle and I hadn't seen each other in over 20 years, but she jumped at the chance to lend her invaluable expertise to Blueprint Earth's work.

While that example of asking for help is pretty obvious, I've also asked for help from some very surprising places. I mentioned in my last post that we have high school age volunteers. I've asked them for help, because social media is moving at a pace that I just can't keep up with. Facebook? Sure, I had that in college. Twitter? Getting the hang of it. Instagram? Uh...what, now? In order to make sure Blueprint Earth's work reaches all of our targeted audiences, we need to get people working with us who know those audiences. So yes, ask a teenager how to use whatever new-fangled tool is going to have the desired effect. Ask a businessperson if they can review your strategy. Ask a person with little formal education (or in our context, no real science education) if the way you're explaining your work makes sense. Assume that everyone has something to teach you, because more often than not you'll find that to be the case. If you're starting an org from scratch, you'll end up viewing every single person you talk to in that light. It's amazing how your perspective will shift.

3. There Is a Solution to Nearly Every Problem. If Not, Change the Problem.

This one also involves a shift in perspective. In the startup world, some days it feels like you're on fire. Every shot you take is nothing but net, every door you knock on opens right up, and every handshake leads to a done deal. The opposite also happens, and those days leave you staring blankly at your computer monitor, wondering what on earth you were even trying to accomplish. I've found that the best way to get around problems that appear immovable is to shift focus. When you're in the heat of running your organization, it's easy to get wrapped up in the day-to-day urgency of what you're attempting. Not everyone you're trying to work with, around, or through has that same urgency, and this can and will prove to be an obstacle at times.

Rather than wasting energy trying to push through every roadblock the moment you encounter it, success can often come from just giving another area attention for a while. Sometimes, the roadblock can come from within, and perhaps you just aren't up to emailing those 20 journalists you've identified for your next PR campaign. Maybe cold-calling another CEO just feels incredibly draining, or that drive to the other side of town to pick up supplies seems too much at this time of day, in all of that traffic. Unless you have a critical deadline within the next few hours for that particular troublesome task, set it aside and work on something else. I've had days when my graphic design brain has been completely useless, so I'll turn my focus to researching grants, or writing a newsletter. Perhaps I don't want to do anything involving a computer, so I'll organize our field equipment (GPS devices, notebooks, measuring tapes, and head lamps don't organize themselves, people). The key here is to keep busy, to keep moving forward. Progress is always welcome, even if it's not in the area you expected.

4. Become a Professional Juggler.

The advice in the previous point would be completely useless if you've given yourself only one or two tasks to accomplish. While a narrow focus may be fine for people on the lower rungs of an organization, once you're at the higher levels it's common to have multiple projects that require your attention. To me, it's as important as breathing. I know that there's an ebb and flow to my style of working, and I know that accommodating that style will optimize my productivity on any given day. That's the true secret to being an effective boss/manager/leader, really. Managing others is all well and good, but knowing how to get the maximum amount of productivity from yourself is what will make your organization a success.

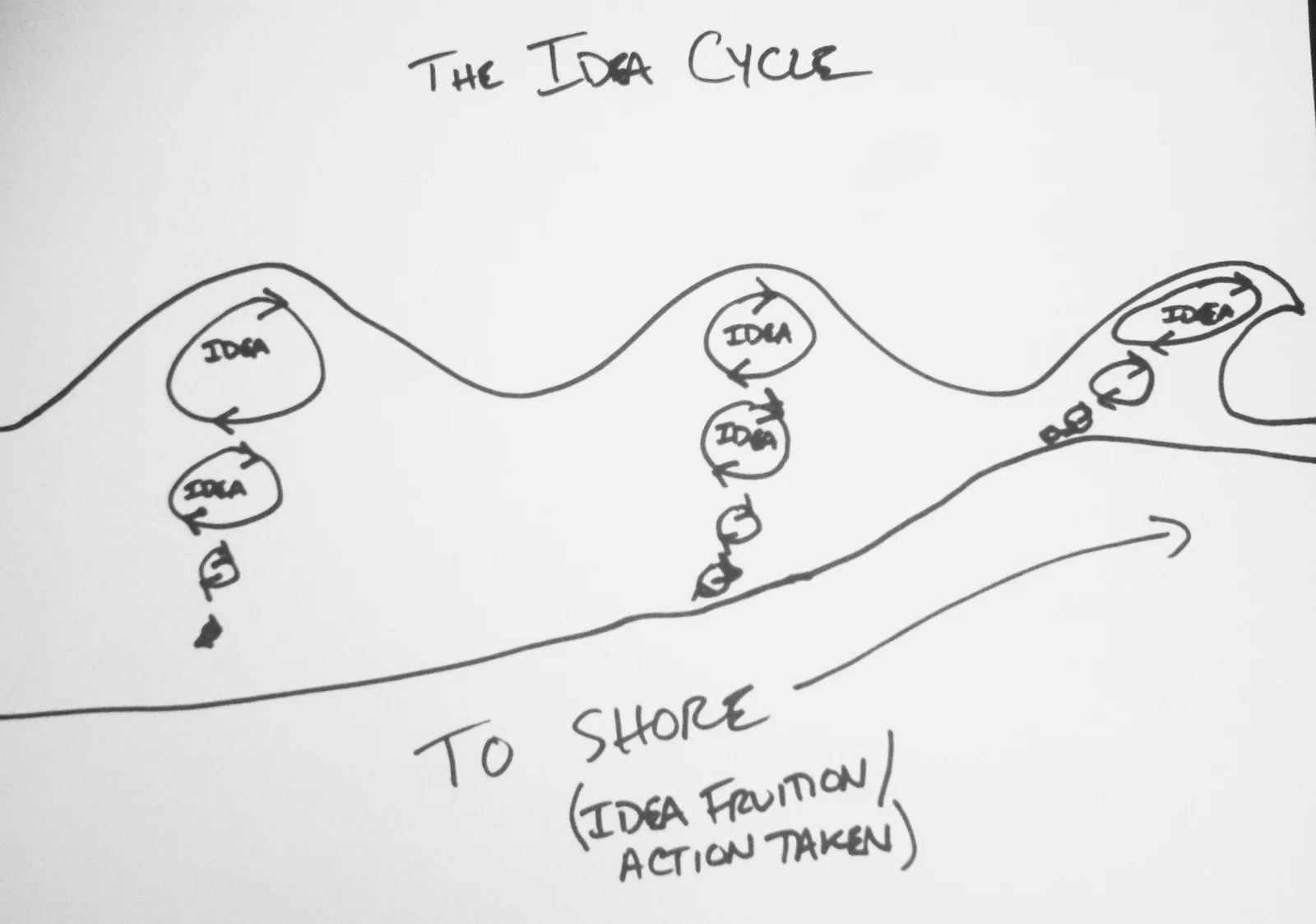

I visualize my own personal productivity as a cycle, and it looks a good deal like the way waves work. I've made this handy diagram for those non-oceanographers reading this: The Idea Cycle.

Note how my previous careers did not include classically trained portrait artist.

Basically, water moves in gyres under the surface. The gyres rotate towards the shore (in my diagram), and when the lowest gyre runs into solid ground, the wave essentially stubs its toe. This propels the wave (or in my case, ideas) forward, causing it to break. Some days, solid ground is nowhere to be found. When that happens, I do whatever I can to keep as many ideas or projects circulating. I know that as long as I keep mentally cycling through the many different projects I'm juggling, things will move toward that solid ground. When the wave breaks, I'll achieve that desired outcome. The key with ideas, as with waves, is constant forward motion.

~Jess